By: Daleyna Abril

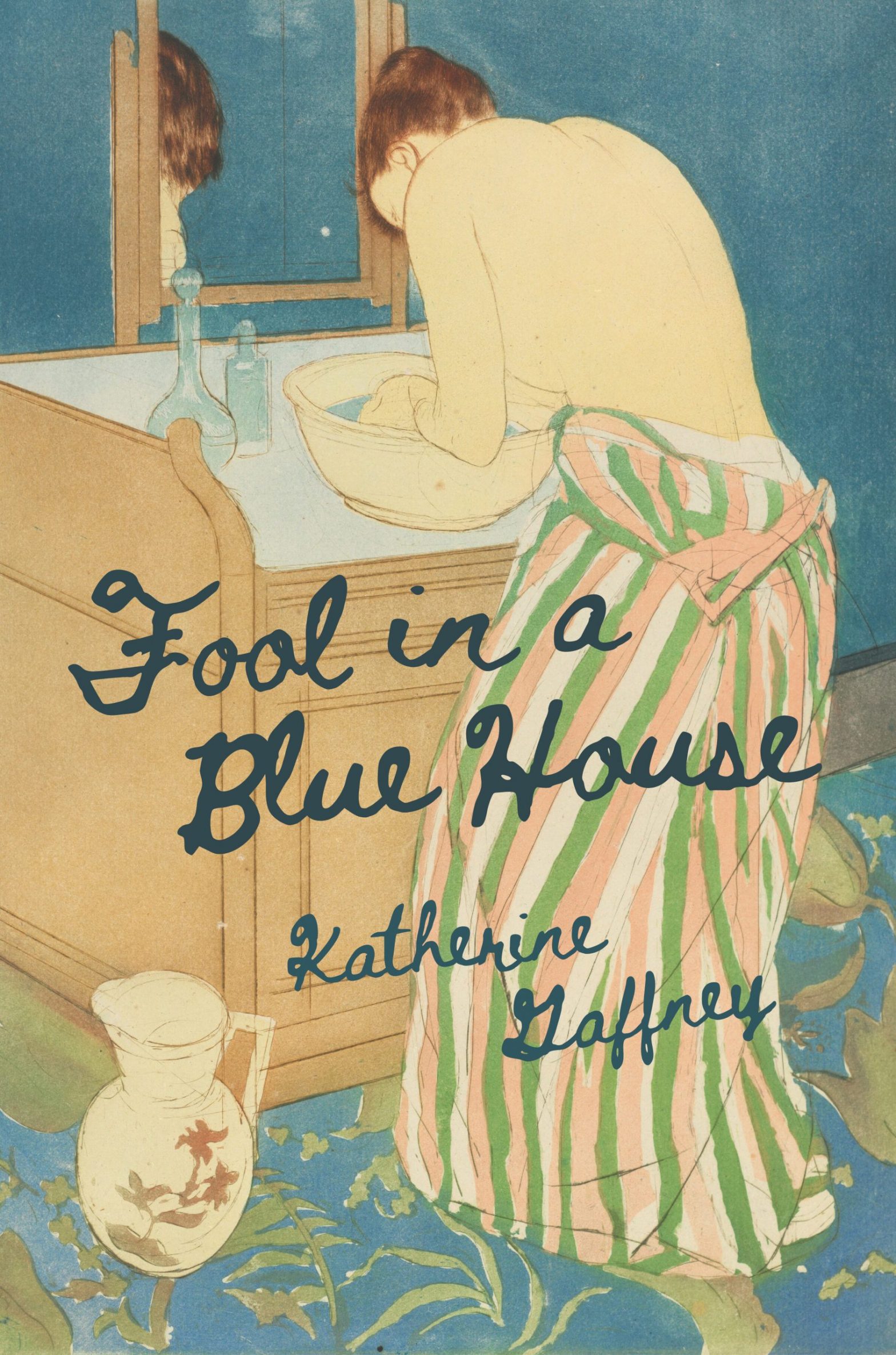

Katherine Gaffney is the recipient of the 2022 Tampa Review Prize for her collection of poems, Fool in a Blue House, forthcoming in 2023.

The following interview was conducted via email.

DALEYNA ABRIL: The Tampa Review judges described Fool in a Blue House as “much a collection of poems as it is a process of intimate discovery—intimacy in relation to love in all its facets and subsequent relationships.” Did you always have a sense that this collection was going to trace love through a lifetime? How did you come to focus on romantic and mother-daughter love?

KATHERINE GAFFNEY: I wrote these poems over the course of five or so years and so perhaps that is where this sense of spanning time stems from? In beginning to write Fool in a Blue House, I took it one poem at a time without clear vision of the project to come. Many of these poems were even written during my MFA, which may also be where that single poem process came from, given the nature of workshop in that environment.

This manuscript has also taken many forms and shapes—in its early stages, it was around 100-pages long. At the end of my MFA, it was titled No One Thought of Birds, but Corey Van Landingham, author most recently of Reader, I, forthcoming from Sarabande Books, thought the title Fool in a Blue House might better capture the heart of the manuscript. And I think she was right. It’s funny how that outside perspective can make all the difference in finding the heart of a manuscript. The title Fool in a Blue House helped me write my way into the manuscript better, rearrange it, and more clearly articulate that tension of tracing love across the romantic and the familial (more specifically and perhaps most dominantly the mother-daughter relationship).

I also think some of the nature of this focus was organic given that I was beginning to navigate this romantic love in a shared domestic space for the first time.

DA: Another recurring theme in this collection is bodily autonomy for the narrator, women, and people with uteruses. Pieces like “A Conversation in Home Depot’s Kitchen Department with a Line from Mrs. Dalloway” and “The World is the Goat Who Ate My Dress Clear Off My Body” depict female rage in a way that was cathartic to read as a woman. What drew you to focus on these topics across the collection? How can these depictions make a change in our world?

KG: Bodily autonomy is something incredibly important to me and perhaps now more than ever before in my lifetime. Acknowledging and embracing rage in certain manners are incredibly important aspects of exploring and identifying the broad spectrum of feminine identity. It’s something many female identifying persons are trained not to engage in. We’re told that rage is not part of the monolith of feminine identity, and I strongly disagree.

I think the threads of horses throughout the book intersect with these concerns in meaningful ways and perhaps that’s something more personal to me, but I think riding horses, witnessing horse behavior, and working alongside the wild impulses in domesticated horses involves a certain controlled empowerment that I think intersects with learning to embrace rage.

DA: Echoing that feminist struggle for bodily autonomy mentioned in the previous question, you compellingly display how the fear of and rebellion against sexual assault binds together generations of women in the poem “Once Read as Ruin.” Why did you choose to spotlight Ebba the Younger and Wilgefortis in this piece? Moreover, why choose to write from multiple different perspectives, including that of the Father?

KG: “Once Read as Ruin” is one of those poems that begins stitching together the threads of horses in this collection, and as you say is very much concerned with bodily autonomy. Bodily autonomy for the speaker/rider as it relates to presentation of the body, particularly after a ride. Bodily autonomy for the horse as it relates to human care—whether brushing a mane or binding a summer sore on a hock.

Ebba and Wilgefortis felt like distant, venerated doubles of the horse and the speaker respectively. For some context, Ebba is the saint that originated the phrase “Cut off the nose to spite the face” in hopes of avoiding assault by invaders. And Wilgefortis is the saint that, in wishing to remain pious and avoid marrying a non-Christian suitor, asked for god’s help and that help came in the form of a beard—a non-feminine form of facial hair.

The why was perhaps a feeling that the pair of us, speaker/rider and horse just didn’t quite feel like the poem was speaking outside of the horse world or outside of my world just yet. Perhaps it was a selfish search for stakes? But I think the result is what you point out, the ability for the piece to address the issue from more than one perspective, more than one voice, which in earlier drafts of the poem would have just been the speaker’s/rider’s voice. The cacophony of voices and varying extreme approaches toward that autonomy from bodily modification helps build the poem’s tension.

DA: One of the poems that piqued my interest was “Hope Chest,” simply because I’d never heard of such a tradition and was immediately curious about it. The act of keeping a hope chest seemed like another example of the patriarchal expectations for a woman’s life. Tell me about what a hope chest is supposed to be compared to what it is to you. Do you think people should keep a hope chest for their futures—for marriage or otherwise?

KG: The story of “Hope Chest” is that before my move to Illinois for graduate school, my mother acquired the hope chest second hand. She told me it would be good for blankets given the cedar lining and briefly explained the object’s history. She sort of implied I shouldn’t tell the history to my partner (unmarried), who I was about to live with, as it felt like a pregnant presence in the house. I don’t think the poem (or I as a maker of that poem) suggests that anyone should or shouldn’t keep hope chests for any particular reason, but more marvels at how patriarchal forces imbue a piece of furniture with expectations. That we are still working to fracture those expectations and demystify the expectations and hauntings that come with not keeping a hope chest, as the 1928 Lane furniture advertisement suggests. So, perhaps it’s a means of further cry for autonomy, not just bodily but in terms of expectation.

DA: Many of these pieces are about intergenerational experiences and traumas between mother and daughter and the struggles the mother faces, such as miscarriages. When it comes to writing about family, do you have any rules or boundaries you put in place? What advice would you give to other young poets who want to write about the intimate experiences of their family members?

KG: I don’t think I am alone when I say that many of my early encounters with intimate significant others often have roots in inherited domestic and intimate partners encounters witnessed growing up, in my case through my parents and grandparents. But I think this is the case for others in observing aunts/uncles with their partners or other parental figures.

My mother’s relationship to motherhood identity and thus her relationship to me is precious as she is one who struggled to carry a child to term and so I think this history puts a certain valence on our relationship that makes it sharp and passionate. So, I think these intergenerational experiences and traumas inform the intensity of intimacy with the family that threads through this collection.

To answer your question about rules or boundaries, I don’t have set rules or boundaries for writing about family. Janice Harrington once said of a poem I wrote about my grandmother’s dementia that the poem may be a more private poem. So, I think there are many poems that may be more private than others. Whether private means we keep them for ourselves and/or for our families or perhaps publish them in journals but not in collections is an intimate question for each poet.

Family is so essential to my identity that I think it would be hard for me to not write about my family and so perhaps it’s a question of genuineness that comes with working to address these topics and themes of intergenerational trauma and hopefully as well some of the buoyant beauties of strength in these traumas, as my mother called the heart monitor company after her heart attack to complain about the design not accompanying large breasts.

So, I think that compass about writing about family is one that comes from within, it is one that is particular to every family dynamic, and my advice would be if you are aware of that precarity than you are likely doing something right in navigating that difficult lacuna.

DA: Fool in a Blue House is your second collection, following the chapbook Once Read as Ruin. How do you feel you’ve grown between these two collections? Did your writing process change between them?

KG: Fool in a Blue House and Once Read as Ruin have some overlap—that is, some of the poems published in the chapbook are published in the full-length collection.

In fact, the title of the chapbook comes from a poem mentioned in this very interview!

For me, the chapbook served as a space to begin finding the beauty of tangled tendrils between poems on a more manageable scale, at least for me and my brain, as I learned to understand the behaviors of my own poems. Perhaps it’s something like learning to lunge a pony versus a fresh-off-the-track 17-hand thoroughbred.

So, I would identify my growth as being able to better commune with the poems, to understand and predict their behaviors like a horse’s particular stare or hip shift that hints at their coming mischief.

I think my writing process changes from poem to poem, so I suppose the answer is yes to your latter question, but I think that occurs as I approach each new poem.

DA: What are you working on now?

KG: I would say I have two separate projects currently. One is a project stemming from the vein of poems concerned with motherhood in Fool in a Blue House, but moving toward my relationship with the identity of motherhood, including hypothetical, imagined motherhood, and continued meditations on some of my mother’s journey into her own motherhood identity.

The other project is one also concerned with family, but this time more historical family narratives. Particularly, this younger project is a sort of docupoetics project about my grandparents’ and uncles’ experiences of the Nazi Occupation of the Netherlands. Working from a personal family archive of letters, a commonplace book, and other documents alongside materials from more public archives, I am writing both poetry and nonfiction to begin to tell this story.

Katherine Gaffney completed her MFA at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is currently working on her PhD at the University of Southern Mississippi. Her work has previously appeared in jubilat, Harpur Palate, Mississippi Review, Meridian, Best New Poets, and elsewhere. She has attended the Tin House Summer Writing Workshop, the SAFTA Residency, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference as a scholar. Her first chapbook, Once Read as Ruin, was published at Finishing Line Press. Her first full-length collection, Fool in a Blue House, won the Tampa Review Prize for Poetry and is forthcoming in 2023.

Daleyna Abril is a junior at the University of Tampa majoring in English and Writing. She is president of UT’s chapter of Sigma Tau Delta, assistant editor for the Neon Art and Literary Magazine, a tutor at the Saunders Writing Center, and a student worker for the UT Press. In her spare time, she writes diversity-focused movie reviews for Incluvie.com.