By: Daleyna Abril

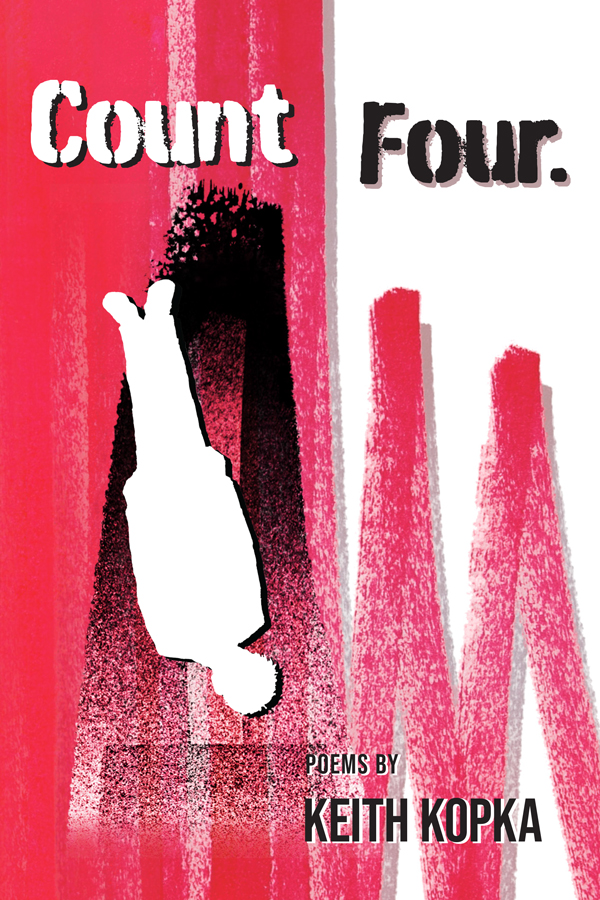

Keith Kopka is the recipient of the 2019 Tampa Review Prize for his collection of poems, Count Four (University of Tampa Press, 2020).

The following interview was conducted via email.

Daleyna Abril: In his review of Count Four, Adrian Matejka describes your poems as “both complicit in and aware of masculinity—how easily it damages, how quickly it becomes a smudged lens for everything around us.” I also found it compelling that the dangers of toxic masculinity are a unifying theme across this collection. I’m interested in the way you conceptualize and portray this concept in your poetry via everything from personal male role models to cowboys to punk rock. What drew you to writing about masculinity in this collection? Why use this concept as your main theme?

Keith Kopka: Honestly, I don’t think I had any choice but to address toxic masculinity as one of the main themes in the collection. Toxic masculinity has become a buzzword, but often the concept isn’t explored beyond the surface gesture of being able to point to something as both toxic and masculine. This oversimplification is a problem because this kind of toxicity is damaging our culture and presenting a large percentage of the population with a dangerous image of how they are supposed to function in relation to their gender. These were the poems I needed to write because they reflect a world I inhabited. A world that was, and still is, filled with young men who fancy themselves rockstars and cowboys. Young men who’ve looked at their fathers and decided that they want to “live fast and die young” rather than slowly drinking or smoking themselves to oblivion. But, as I hope these poems convey, the actions around these fantasies can become much more than youthful indiscretions when there is no healthy role model in sight. People lose themselves and never truly develop beyond adolescence, or, worse, they harm someone else or themselves because of the choices they make concerning a toxic masculine “ideal” that does not exist. This has been one of the ongoing sagas of masculinity in our culture, and we’ve spent too much time either ignoring it or oversimplifying how we vilify it. I wanted these poems to shine a light into this dark corner of our cultural psyche and force readers to confront how we are all impacted by it.

DA: With the recent rise of antisemitism in popular culture, I found “Square Dance Conspiracy” to be extremely relevant right now. As someone who cares deeply about the ways white supremacy is ingrained in America’s systems and culture, I appreciated this direct address to Henry Ford. What inspired you to write this poem to him, and has its meaning evolved for you since you originally wrote it?

KK: Like many people, I had to awkwardly attempt to learn square dancing in my middle school gym class, but I never questioned it at the time. It just seemed like something one did. It was a strange rite of passage. I don’t think the gym teachers knew why it was part of the curriculum. One night, I was having a conversation with some friends, and we realized that we were all forced to learn this archaic dance, but none of us had ever asked ourselves why. A quick Google search revealed this whole horrific history, and I knew I had to write the poem.

At first, the piece was more concerned with the absurdity of Ford’s obsession. Still, the more I reflected on his motivations and what he’d accomplished, the more I could see the resonance in what’s been happening in places like Charlottesville, and the poem evolved from there. As we all know, white supremacist ideas and antisemitism have been an unfortunate consistency across history, but there is no doubt that in recent years these fringe ideologies have gained more mainstream traction and have been emboldened in disturbing ways. One of the only good things about instances where these kinds of ideas are revealed so blatantly is that one can point to them and clearly say, “this is wrong” and set oneself in opposition. However, it isn’t as easy to do this when ideology is couched in elements of culture that seem harmless or absurd. Instances like this are also when ideology can become especially dangerous. Ford knew this, and his decision to use something like dance to wage his culture war was purposeful. He wanted to indoctrinate people, and he needed to be held accountable. The fact that this poem is a direct address to him is my attempt at that. However, it is also an attempt to remind readers that dangerous ideologies can take on many forms, so we must continue to be vigilant.

DA: The second section of Count Four is broken up into poems about your experience touring as a punk rock musician. The poems in this section are named for different cities, different moments during the tour, all chock full of the stereotypical violence and rebellion expected from such a life, but also peppered with quieter moments of questioning and remembrance of another life. Tell me about your process writing this section. How did you decide on what moments to focus on? What kind of story did you want to tell?

KK: When I was touring, I used to keep notes on my phone about my experiences, but they weren’t poems yet. “Tour,” as it stands now, began to take shape a few years after I stopped playing music in any consistent way. Being outside of that world for a while was necessary to put the pieces together and present the experience to readers in a real way. It was this kind of emotional authenticity that I was most concerned about when writing the sequence rather than presenting any linear story. As you note, there are things in the poem that one might expect in a “rock n’ roll” narrative like “Tour,” but finding ways to present familiar tropes and then subvert readers’ expectations was also an essential element of the narrative I was trying to create. There are so many cultural expectations around musicianship, touring, sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll that the poem would not function if it didn’t acknowledge stereotypes before attempting to work against them. In many ways, this poem is an elegy, but it is also a trauma narrative. Many people romanticize the musician’s lifestyle, and this poem undermines this romantic ideal by presenting readers with a speaker trapped by their own designs.

DA: Many of these poems are deeply personal stories. I believe poetry as a medium can often be diaristic and confessional as a mode where writers can be most intimate with their readers. However, this writing process can also pose a risk to the writer’s mental health. How have you managed the balance between sharing about private matters and taking care of your mental health?

KK: This is an important question. I am not a mental health professional, but I have always found the process of writing confessional poems cathartic. Poetry has provided me with a way to process trauma in a healthy and controlled manner. Yes, the poems in Count Four are deeply personal, but they are still poems, which means that they are a piece of art, and no piece of art is the entire truth. Instead, it’s a version of the truth curated for an audience. This curation process has allowed me to let go of some of the expectations and pressures that come with presenting the intimate details of one’s life. It’s definitely intimidating, but this understanding has provided me with a way to separate myself from the art, no matter how personal the story is. In other words, all these poems are true, but they are also all lies. I find this thought comforting, and it allows me to keep pushing poems to often difficult or uncomfortable places while maintaining my mental health.

DA: I always pay attention to titles and find myself curious about their origins. Many of your poems have fantastic, punchy titles that immediately hook you in—some of my favorites include “Ancient Astronaut Theorists,” “You, Strung,” “Square Dance Conspiracy,” and “After Talking It Over with His Ghost, My Father Tells Me He’s Sick.” I’m most interested in how you chose the title for this collection: Count Four. It’s a simple phrase mentioned once in “All We Do Is Begin,” the measure musicians count before playing. What is the significance of “count four” to you? Why does it make a good title for this collection?

KK: I think that you hit the nail on the head when you referenced musicians counting in a song. This collection spends a lot of time exploring my life as a musician, so the title connected for me thematically on that level. Still, as you noted, it is more specifically what happens at the start of a song. Since this is my first collection, I was thinking about Count Four as a beginning, an origin story, and the thought of counting myself and my readers into these poems felt like a fitting gesture.

DA: What are you working on now?

KK: I’m hard at work on my second collection, which interrogates the idea of survivor’s guilt while expanding on the themes of toxic masculinity introduced in Count Four. This new book is especially interested in how this kind of trauma is passed down and inherited through cultural and familial violence.

Keith Kopka is the recipient of the 2019 Tampa Review Prize for his collection of poems, Count Four (University of Tampa Press, 2020). His poetry and criticism have recently appeared in Best New Poets, Mid-American Review, New Ohio Review, The International Journal of the Book, and many others. He is also the author of the critical text, Asking a Shadow to Dance: An Introduction to the Practice of Poetry (GRL 2018). Currently, he’s an Assistant Professor and Director of the low-res MFA at Holy Family University in Philadelphia.

Daleyna Abril is a junior at the University of Tampa majoring in English and Writing. She is president of UT’s chapter of Sigma Tau Delta, assistant editor for the Neon Art and Literary Magazine, a tutor at the Saunders Writing Center, and a student worker for the UT Press. In her spare time, she writes diversity-focused movie reviews for Incluvie.com.