By: Daleyna Abril

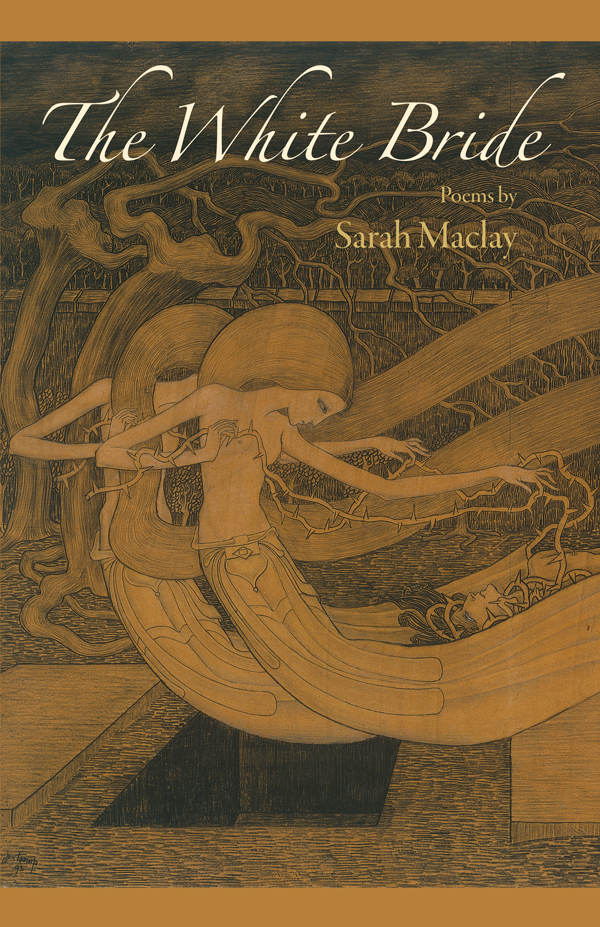

Sarah Maclay is the recipient of the 2003 Tampa Review Prize for Poetry for her collection of poems, Whore (University of Tampa, 2004). She has also published two additional collections with the University of Tampa Press: The White Bride (2008) and Music for the Black Room (2011). Her newest collection, Nightfall Marginalia, is out from What Books Press (2023).

The following interview was conducted via email.

Daleyna Abril: How would you describe this newest collection, Nightfall Marginalia, to readers?

Sarah Maclay: It’s a book of mostly nocturnes and ekphrastics—writing from dream, from the liminal, from art, with a few stabs at formal or modal experimentation—a somewhat skewed abecedarian, some exploded OuLiPo, a list poem that’s sort of a docupoem, taking in the housing precarity of LA, with plenty of bows to other books and films, even a little parallax view, where the same event is seen twice from different perspectives and times. It’s a book written from a more autumnal time of life than my earlier collections, but still dancing in the romantic and existential shadows that I can’t seem to shake. A poet friend called a clutch of these poems a grimoire—a book of spells. Let’s hope she’s right. Thinking of it that way gave me a great gust of permission.

DA: You’ve written four collections prior to this, with the last one—The “She” Series: A Venice Correspondence—published in 2016. Would you say your writing process has grown or changed in any way from your previous collections? Could you describe the process of compiling these poems together for Nightfall Marginalia?

SM: One thing I tried in this collection that I hadn’t much before was delving into long, narrative poems. Even though I tend to think of those, like the shorter lyric ones and prose poems in this and earlier collections, as in service of a lyric moment, ultimately, it was actually great fun to explore this mode, to keep seeing what would happen next if I went on—and it was also one of the ways I worked with ekphrasis, that is, by either inhabiting one of the figures of a work and allowing the poem to evolve as a persona poem, or by getting involved in a body of work I felt close to and allowing the many works to speak as a kind of story where I felt somewhere between an omniscient and limited-omniscient (close 3rd) narrator. What propelled me the most, whenever I got stuck, was just going back and back and back again to the work/s, into the details, and really noticing them, and sometimes even allowing the background setting to become its own character. Readers tell me that some of these poems have a sort of storybook or fairy-tale-like quality, which feels really right to me for a book that is so given to the world of the night.

About the process of putting this together—I took my time. The poems, mostly, were not coming that frequently, though I was really aided by a City of LA Individual Artist Fellowship, in particular, that demanded enough new work to present a 20-minute reading. Many of those poems are part of this book, though not all. I was also taking care of my father for long swaths of this time, during his last years, so during those times I had to be hypervigilant even at night, and there were only a few times where I was so assured of his sleep and safety that I could burrow into the poems for an hour or two. I was also committed to a phase of living first, writing only in the margins of that living (an active part of how I think of the title), during this later midlife time (“autumnal,” let’s say), so though it was great solace to keep returning to these poems, it wasn’t always front and center of what had to be done, on any given day. Toward the end, when I was asked by one of the editors at my press to consider adding more poems, I surprised myself by adding one I began more than forty years ago and had only gotten to a place that felt right very recently, as well as one or two others I thought I’d already discarded, and then I also shuffled the orchestration, which had felt finally super-solid and somewhat hard-won for that, into something more symphonic and emotionally dynamic, so even if there’s ultimately something that can feel like a subterranean narrative, it’s not from strictly adhering to any particular chronology about how and when the poems were written. This editor also suggested ending with the poem that now ends the book, something I think I had resisted earlier as far too sad, but I think he was right—and possibly prescient.

Like the dream, art is another place to go that still allows us transport—and where we can sometimes be even more fully ourselves—in addition to (and often in concert with) the events we’re living through.

DA: The majority of these poems are ekphrastic, inspired by everything from Edvard Munch’s art to a screensaver. Can you speak to what draws you to the ekphrastic poem and why it comprises such an essential aspect of this collection?

SM: It’s not that I haven’t gone there before, but that somehow I allowed so much of this book to be centered around this kind of work. Like the dream, art is another place to go that still allows us transport—and where we can sometimes be even more fully ourselves—in addition to (and often in concert with) the events we’re living through. Perhaps, one could say, it even becomes one of those events, if we let it—or an illuminating counterpoint to life events. That certainly felt true for me as I was writing these poems. I think sometimes, too, there’s enough respite in being able to fully enter art, for a time, that there is also a kind of relief available from the difficulties of the daily, as much as the art itself might speak to them. I find this true whether the work of art is a painting, or a photograph, or a film, if it’s one that resonates. That’s the key thing, I think—if you’re interested in moving toward a practice that centers the ekphrastic, for a time, you just need to be alert to what’s pulling you in and making you want to write. Just listen for that—like with your skin, as well as your inner ear. It won’t be everything. And it won’t feel random, however wide the variation in the stimulus.

DA: These poems are spent in liminal spaces, in autumn, in gray, in the twilit waking dream, in nightfall, and in the margins. What do you think writing from liminality and marginality can offer poets and their readers?

SM: For me, as a poet, it’s sort of where I live. It’s one of the only places I can write from that results in anything that feels like a real poem to me, and I know it’s what I most respond to, and am most called to, in the poems by other writers that most reach me and transport me. It’s not that this means that all other daily life is squeezed out, but rather that maybe it’s all approached from this other angle that helps us move toward the real mystery of it all—those ineffable places that nonetheless have such presence that they feel most real. Paradoxically, perhaps, in poems, we approach them through the senses.

DA: Many reviews of your work and this collection in particular use the word “sensual” as description. What does the word “sensual” mean to you? How does Nightfall Marginalia capture it?

SM: There are two things—one, that I hope, as a poet, with any luck, to be sensorially alive and receptive to all the phenomena we can perceive—see, hear, smell, touch, taste—and perhaps that this kind of openness, while writing and in the poems that result, can progressively shift our framework for how to be, or allow us to be more completely in the presence of whatever it is we’re encountering, whether “in real life,” in a painting, or in a dream. The other thing is that the work is largely informed by eros, and I’d hope that somehow, in those poems, I am able to get across something about how that experience feels in a way that people can more fully enter. Often, as I tell my students, this isn’t done by giving an abstract name to something, especially to an emotion, but by evocation (through imagery and metaphor, largely) that allows us to sense something maybe even richer and more ambiguous and complex than any name we’d be tempted to label it with.

DA: What are you working on now?

SM: I’ve just had a chapbook picked up—The H.D. Sequence, A Concordance—by a new micro-press here in Los Angeles, Walton Well. It’s also something that took a long time to complete, even though it was begun sort of ferociously in a many-poems-all-at-once frenzy, some years ago. I’d been teaching H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), whose poems had long spoken to me, during a season of sudden emotional duress, and many phrases from the center of her work in Trilogy became little lifeboats, routes toward incipient healing, and so found their way into the work as poem titles or sometimes borrowed language within a poem. In this way, it was like being in some kind of conversation with that part of her work, and though I know this bends the word a little, I can’t think of “Concordance” now without special emphasis on the last syllable. In a way, it was like I was dancing with her words, which were also very centering. The book gets pretty quirky, I’d say, at times. It’s also fed by dream and artwork, as happens with me. It just felt really distinct, this work, as it found a kind of idiom, from other poems of mine, though the emotional territory is similar (if, at times, more dire), and I always saw it as a standalone chapbook rather than a section of a larger collection, so I’m really pleased that it now has a home. It took a long time to complete because, after that initial rush of poems, I was so rarely in such raw turmoil that it wasn’t really possible to jimmy a place like that to work from—an emotional state— or, on the other hand, I would get these notions—about trying this or that—that wouldn’t really work, because they were coming from too conceptual a place, but I finally realized that I was farther along than I’d thought, and somehow I was finally able to see it again clearly enough to be able to finish some of the waiting germs of poems and to trust the few much newer things that felt right for this project. So now we’re starting to think about cover art, and I’m excited to get back into the book production process.

***

Before I sign off here, I just need to end with a little salute and lots of gratitude: it was a joy to work so closely with Richard Mathews on my first three full-lengths, from UT Press. His love of the art of book design, as well as his patience and courtliness in all correspondence about the making of the books, and the way he welcomed my input, even beyond things the contract officially covered, was such a rich and satisfying experience, down to the choices of matte finishes and the feel of the paper. Whenever the first new books arrived, they were just so beautiful and enticing, as objects—as made things—that I literally wanted to rub their surfaces like in those tales of the magic lanterns from which some genie would appear. So . . . a big hug and thanks to Richard and to the press, for believing in me and working with me! And to Martha Serpas, who first fished my initial manuscript out of a box and kept reading it out loud to Audrey Colombe, who found me at AWP the next year, when the book was freshly out, and led me to the table at the book fair, and Donald Morrill, who drove me across the bay to the Dali Museum in St. Pete when I visited, and to the tireless Sean Donnelly. And now a big thanks to you and to Wesley!

Sarah Maclay’s fifth collection is Nightfall Marginalia (What Books Press, 2023). Her poems and essays, supported by a Yaddo residency and a City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship and awarded the Tampa Review Prize for Poetry and a Pushcart Special Mention, among other honors, have appeared in APR, FIELD, Ploughshares, The Tupelo Quarterly, The Writer’s Chronicle, The Best American Erotic Poetry: From 1800 to the Present, Poetry International, where she served as Book Review Editor for a decade, and beyond. She teaches at LMU and offers workshops at Beyond Baroque, roaming between LA and her native Montana.

Daleyna Abril is a senior at the University of Tampa majoring in English and Writing. She is president of UT’s chapter of Sigma Tau Delta, editor-in-chief of the Neon Art and Literary Magazine, a tutor at the Saunders Writing Center, and a student worker for the UT Press. In her spare time, she posts food reviews on her blog, daleynaeats.com. You can find her writing portfolio at daleyna.com.